When Gods Are Rewritten: Faith, Fiction, and the Forest in Kantara: Chapter 1

Where Sanatan wisdom meets cinematic imagination — and the line between reverence and reinterpretation begins to blur.

In the silence between drumbeats, the forest still remembers what we have forgotten

The Fire in the Forest

There’s a fire in the forest again.

Torches flicker, drums thunder, the conch reverberates — and in the haze between trance and devotion, a spirit descends.

In Kantara (2022), that moment wasn’t mere cinema. It felt like initiation — the invocation of something older than language: the rhythm of soil, sweat, and surrender.

But its prequel, Kantara: Chapter 1, walks a different path — filled with celestial wars, black magicians, and a hero’s transcendence into Mahadev energy.

The question that rises from its embers is ancient and urgent:

When art touches the divine, does it enlighten — or begin rewriting what is sacred?

The Grammar of the Sacred in Sanatan Dharma

In the Sanatan worldview, divinity is not confined to temple walls or scripture. It breathes in soil, streams, lineage, and collective memory.

Every village, family, and seeker carries its own fragment of the cosmic whole through four living archetypes:

Gram Devta — the guardian of the village or land. Protector of crops, wells, and boundaries. The Gram Devta’s festival unites everyone — across caste, creed, and sect — because the deity belongs to the land, not to any single group. When a village honors its Devta, it honors its ecology and community together.

Kul Devta / Kul Devi — the family deity, invoked at births, marriages, journeys, and illness. The ancestral energy binding generations — the witness of a lineage’s karma.

Kshetrapala — the guardian of sacred territory, often at temple thresholds or forest edges, ensuring the balance between the sacred and the worldly.

Ishta Devta — the personal deity or energy closest to one’s heart, the compass of one’s sadhana, chosen not by dogma but by resonance.

Together they form the grammar of the sacred — a decentralized, relational spirituality where the divine is both intimate and infinite.

One doesn’t go to God here — one lives with the divine, as part of daily ecology.

Throughout India, Gram Devta festivals remain among the few spaces where social divisions dissolve. The entire village cleans the shrine, decorates the sacred grove, and joins in procession. The cobbler and the priest, the landowner and the laborer — all offer lamps to the same soil. These rituals are living reminders that spirituality in Sanatan Dharma is not institutional — it’s participatory.

When Faith Meets Frame

The first Kantara captured this pulse with uncanny fidelity.

Its Daiva wasn’t CGI divinity — he was presence: fierce, playful, protective. The film’s strength lay in its ambiguity; it didn’t sermonize, it invoked.

But Kantara: Chapter 1, set centuries earlier, trades that lived sacredness for mythic spectacle. It imagines the birth of the sacred pact itself — the origin of the Daiva, the finding of the sacred stone, the tension between tribal devotion and royal power.

The canvas is magnificent. Yet with grandeur comes distortion.

By introducing the trope of Daivas under control of black magicians or dark forces, the film alters the metaphysical hierarchy. In the folklore it draws from, a Daiva is the light that dissolves darkness — never its captive. The forest spirit is not possessed; he possesses — not in frenzy, but as the living bridge between man and divine order.

The Distortion of the Divine

Art has the right to reinterpret myth.

But does that right extend to reversing the essence of what myth represents?

When Kantara: Chapter 1 portrays Daivas subdued by shadowy powers, it unintentionally domesticates the divine — making gods behave like mortals for the sake of narrative tension. This inversion isn’t blasphemy; it’s spiritual dissonance.

Because within Sanatan philosophy, the divine cannot be conquered by the profane.

Darkness is not a rival force — it’s the absence of remembrance.

To suggest otherwise confuses metaphysics for melodrama.

And yet, for global audiences — many encountering these living traditions for the first time through cinema — the portrayal may become a substitute for reality. That’s where art turns pedagogical, whether it intends to or not.

Faith, Commerce, and the New Market of Myth

Before we speak of sacred responsibility, it’s worth looking at the scale of what’s unfolding on screen — and off it.

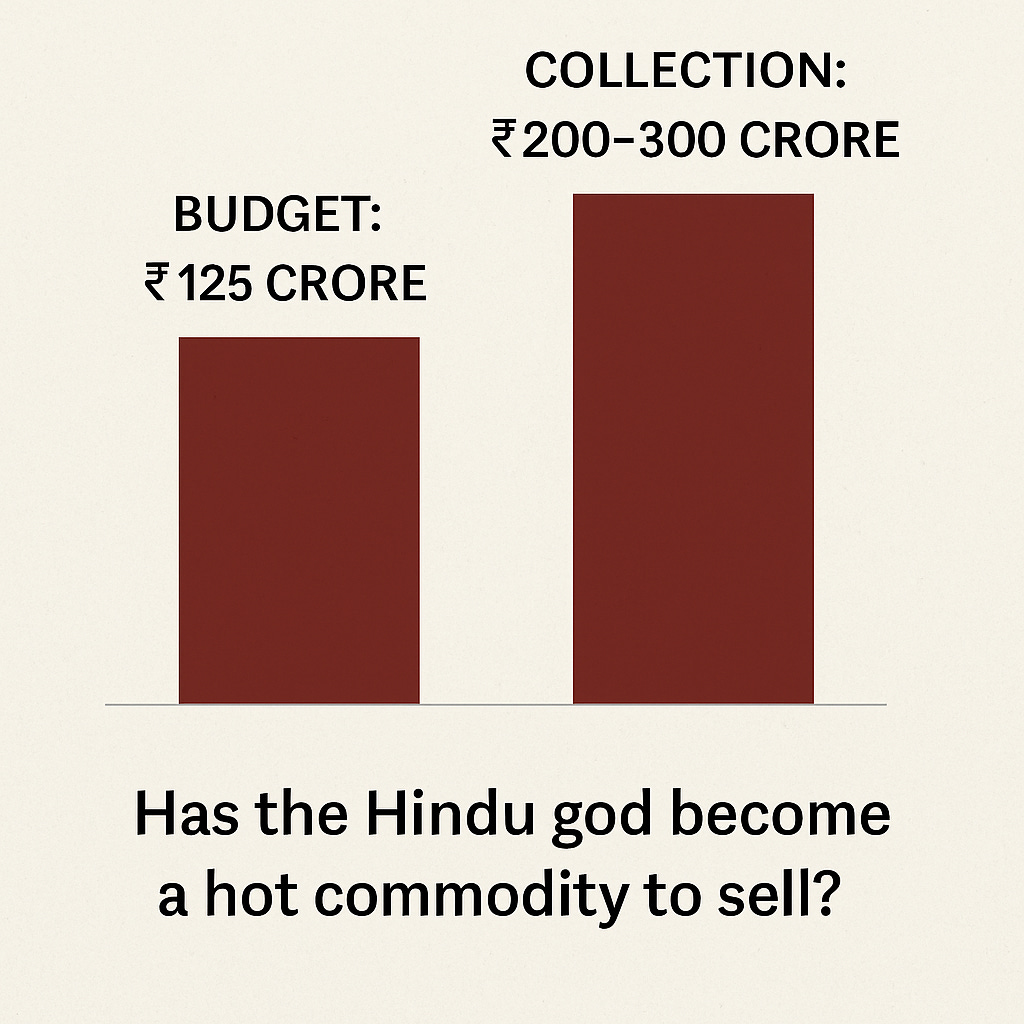

Budget: ₹ 125 Crore

Collection (First 6 Days): ₹ 200 – 300 Crore and still counting

In just six days, Kantara: Chapter 1 has reportedly doubled or even tripled its production cost, amassing enormous box-office revenue both in India and among the Indian diaspora abroad.

The question writes itself:

Have the gods — especially the Hindu gods — become the hottest commodity to sell?

Cinema today isn’t merely retelling myth; it’s monetizing faith, packaging devotion into spectacle. And while there’s no harm in art inspired by the sacred, the line between reverence and retail is growing dangerously thin.

Is the divine being remembered — or repurposed for mass appeal?

That pause between profit and prayer might be the truest reflection of where culture stands today.

The Hero Who Becomes Mahadev

Rishab Shetty’s protagonist — a Naga Sadhu-warrior channeling Mahadev’s energy — is visually spectacular. The ascetic fury, the invocation of Rudra, the transcendence sequence — all echo the idea of divine descent (avatar).

But one wonders: does the film show man merging with God, or man saving the gods?

In the Shiva Purana, Mahadev isn’t a rescuer in the human sense; He is the stillness that witnesses creation and destruction alike. To “become Shiva” means not triumph but dissolution.

Chapter 1 sometimes risks mistaking surrender for conquest — turning enlightenment into a duel. The question isn’t artistic license; it’s metaphysical literacy. In older myths, the divine act was always an unveiling, not a rescue mission.

Hidden Depths and Mythic Continuity

A few elements of Kantara: Chapter 1 deepen its mythos and deserve appreciation:

Set in 300 CE during the Kadamba dynasty, it roots the legend in historical soil — where tribal worship and royal power coexisted uneasily.

The origin of the sacred stone — the vessel of the forest spirit — becomes a metaphor for continuity: how matter can preserve memory.

Ecological divinity — the reminder that nature retaliates when disrespected — preserves the heart of the first film.

Even through spectacle, Shetty holds to the idea that the forest is not background but a breathing deity — a truth easily forgotten in modern storytelling.

The Sacred and the Screen

Perhaps the deeper question isn’t whether Rishab Shetty misread the myth — but whether we still know how to read it.

When we turn living deities into cinematic characters, we exchange the mystery of reverence for the safety of story. The first Kantara allowed mystery to remain. The prequel explains everything — and in explanation, some of the sacred seeps away.

Yet, Shetty’s own journey deserves reverence. From selling mineral water, driving cars, and selling tea pouches to creating one of India’s most ambitious spiritual sagas — his rise is itself a testament to tapasya. Kantara: Chapter 1 is visually breathtaking — a hymn painted in flame and dust.

Still, fiction, however grand, must tread gently on faith.

Belief — whether tribal, rural, or urban — is not a mythic accessory; it is lived heritage. When filmmakers borrow living gods, they borrow responsibility too.

Conclusion: Between Asuras and the Artist

In ancient lore, when Asuras overpowered the Devtas, creation trembled.

Then arose cosmic forces — Vishnu as Narasimha, Devi as Durga, Shiva as Rudra — to restore dharma.

These were not battles of good and evil alone, but of consciousness and ignorance, of remembering and forgetting the divine within.

Shiva and Shakti dwell in each of us — masculine awareness and feminine energy, forever entwined. The artist’s task, like the seeker’s, is to keep that inner polarity in balance.

So the question that remains — not of theology but of artistic dharma — is this:

When Kantara: Chapter 1 shows Gram Devtas under the control of black magicians, does it help new audiences bridge understanding, or does it distort the very spiritual order even Asuras once feared to breach?

Is it creative freedom — or an overreach disguised as imagination?

Perhaps the forest itself holds the answer.

Its silence reminds us that stories may evolve, but sanctity does not.

And if the Daiva ever needs saving, it isn’t the deity who has fallen —

it is our remembrance of the sacred that must rise again.

If this reflection spoke to you, share it forward — faith deserves dialogue, not silence

What a thought-provoking post! Your deep analysis has definitely invoked my curiosity regarding both Kantara 1 and 2 movies. I will definitely watch them, and then I will be in a better position to comment.

Thanks alot Nilambari for your appreciation. Surely do watch and share your unique insights